Other Sites:

Robert J. Robbins is a biologist, an educator, a science administrator, a publisher, an information technologist, and an IT leader and manager who specializes in advancing biomedical knowledge and supporting education through the application of information technology. More About: RJR | OUR TEAM | OUR SERVICES | THIS WEBSITE

RJR Recommendations

Bibliographies

(with links to sources)

Keeping up with the literature can be challenging. Here we offer several automatically-created bibliographies on selected topics, with links out to the original document (via the publisher's DOI), to PubMed, to Google Scholar, etc.

The bibliographies are updated regularly and are sorted to show the

most recent at the top. For long bibliographies the link is to a page

containing only the most recent 100 entries, with a Bibliography

Options menu allowing access to a page with the remaining

entries. These additional pages can be very large and slow to load,

but they can be valuable if you are interested in a comprehensive

listing.

The options menu also allows you to download the entire bibliography

in bibtex format, for easy loading into reference-management software.

The topics are chosen because they interest me, but I would be

happy to consider adding additional topics.

Contact me

with any suggestions.

covid-19

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:42

60601

citations

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2), a virus closely related to the SARS virus. The disease was discovered and named during the 2019-20 coronavirus outbreak. Those affected may develop a fever, dry cough, fatigue, and shortness of breath. A sore throat, runny nose or sneezing is less common. While the majority of cases result in mild symptoms, some can progress to pneumonia and multi-organ failure. The infection is spread from one person to others via respiratory droplets produced from the airways, often during coughing or sneezing. Time from exposure to onset of symptoms is generally between 2 and 14 days, with an average of 5 days. The standard method of diagnosis is by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) from a nasopharyngeal swab or sputum sample, with results within a few hours to 2 days. Antibody assays can also be used, using a blood serum sample, with results within a few days. The infection can also be diagnosed from a combination of symptoms, risk factors and a chest CT scan showing features of pneumonia. Correct handwashing technique, maintaining distance from people who are coughing and not touching one's face with unwashed hands are measures recommended to prevent the disease. It is also recommended to cover one's nose and mouth with a tissue or a bent elbow when coughing. Those who suspect they carry the virus are recommended to wear a surgical face mask and seek medical advice by calling a doctor rather than visiting a clinic in person. Masks are also recommended for those who are taking care of someone with a suspected infection but not for the general public. There is no vaccine or specific antiviral treatment, with management involving treatment of symptoms, supportive care and experimental measures. The case fatality rate is estimated at between 1% and 3%. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared the 2019-20 coronavirus outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). As of 29 February 2020, China, Hong Kong, Iran, Italy, Japan, Singapore, South Korea and the United States are areas having evidence of community transmission of the disease.

PUBMED QUERY: ( SARS-CoV-2 OR COVID-19 OR (wuhan AND coronavirus) AND review[SB] )NOT 40982904[pmid] NOT 40982965[pmid] NOT 35908569[pmid] NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Long Covid

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:51

8706

citations

Wikipedia: Long Covid refers to a group of health problems persisting or developing after an initial COVID-19 infection. Symptoms can last weeks, months or years and are often debilitating. Long COVID is characterised by a large number of symptoms, which sometimes disappear and reappear. Commonly reported symptoms of long COVID are fatigue, memory problems, shortness of breath, and sleep disorder. Many other symptoms can also be present, including headaches, loss of smell or taste, muscle weakness, fever, and cognitive dysfunction and problems with mental health. Symptoms often get worse after mental or physical effort, a process called post-exertional malaise. The causes of long COVID are not yet fully understood. Hypotheses include lasting damage to organs and blood vessels, problems with blood clotting, neurological dysfunction, persistent virus or a reactivation of latent viruses and autoimmunity. Diagnosis of long COVID is based on suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection, symptoms and by excluding alternative diagnoses. Estimates of the prevalence of long COVID vary based on definition, population studied, time period studied, and methodology, generally ranging between 5% and 50%. Prevalence is less after vaccination.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "long covid"[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Long Covid: Review Papers

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:52

1853

citations

Wikipedia: Long Covid refers to a group of health problems persisting or developing after an initial COVID-19 infection. Symptoms can last weeks, months or years and are often debilitating. Long COVID is characterised by a large number of symptoms, which sometimes disappear and reappear. Commonly reported symptoms of long COVID are fatigue, memory problems, shortness of breath, and sleep disorder. Many other symptoms can also be present, including headaches, loss of smell or taste, muscle weakness, fever, and cognitive dysfunction and problems with mental health. Symptoms often get worse after mental or physical effort, a process called post-exertional malaise. The causes of long COVID are not yet fully understood. Hypotheses include lasting damage to organs and blood vessels, problems with blood clotting, neurological dysfunction, persistent virus or a reactivation of latent viruses and autoimmunity. Diagnosis of long COVID is based on suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection, symptoms and by excluding alternative diagnoses. Estimates of the prevalence of long COVID vary based on definition, population studied, time period studied, and methodology, generally ranging between 5% and 50%. Prevalence is less after vaccination.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "long covid" AND review[SB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Species Concept

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 02:00

2406

citations

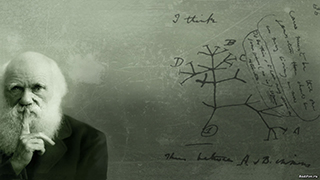

Wikipedia: The species problem is the set of questions that arises when biologists attempt to define what a species is. Such a definition is called a species concept; there are at least 26 recognized species concepts. A species concept that works well for sexually reproducing organisms such as birds is useless for species that reproduce asexually, such as bacteria. The scientific study of the species problem has been called microtaxonomy. One common, but sometimes difficult, question is how best to decide which species an organism belongs to, because reproductively isolated groups may not be readily recognizable, and cryptic species may be present. There is a continuum from reproductive isolation with no interbreeding, to panmixis, unlimited interbreeding. Populations can move forward or backwards along this continuum, at any point meeting the criteria for one or another species concept, and failing others. Many of the debates on species touch on philosophical issues, such as nominalism and realism, and on issues of language and cognition. The current meaning of the phrase "species problem" is quite different from what Charles Darwin and others meant by it during the 19th and early 20th centuries. For Darwin, the species problem was the question of how new species arose. Darwin was however one of the first people to question how well-defined species are, given that they constantly change.

PUBMED QUERY: ( ("species concept"[tiab:~6] OR "species concepts"[tiab] OR "species problem") NOT "invasive species" ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Archaea

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:30

3606

citations

In 1977, Carl Woese and George Fox applied molecular techniques to biodiversity and discovered that life on Earth consisted of three, not two (prokaryotes and eukaryotes), major lineages, tracing back nearly to the very origin of life on Earth. The third lineage has come to be known as the Archaea. Organisms now considered Archaea were originally thought to be a kind of prokaryote, but Woese and Fox showed that they were as different from prokaryotes as they were from eukaryotes. To understand life on Earth one must also understand the Archaea .

PUBMED QUERY: ( archaea[TITLE] OR archaebacteria[TITLE] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Biodiversity and Metagenomics

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:30

17533

citations

If evolution is the only light in which biology makes sense, and if variation is the raw material upon which selection works, then variety is not merely the spice of life, it is the essence of life — the sine qua non without which life could not exist. To understand biology, one must understand its diversity. Historically, studies of biodiversity were directed primarily at the realm of multicellular eukaryotes, since few tools existed to allow the study of non-eukaryotes. Because metagenomics allows the study of intact microbial communities, without requiring individual cultures, it provides a tool for understanding this huge, hitherto invisible pool of biodiversity, whether it occurs in free-living communities or in commensal microbiomes associated with larger organisms.

PUBMED QUERY: biodiversity metagenomics NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Horizontal Gene Transfer

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:30

15336

citations

The pathology-inducing genes of O157:H7 appear to have been acquired, likely via prophage, by a nonpathogenic E. coli ancestor, perhaps 20,000 years ago. That is, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) can lead to the profound phenotypic change from benign commensal to lethal pathogen. "Horizontal" in this context refers to the lateral or "sideways" movement of genes between microbes via mechanisms not directly associated with reproduction. HGT among prokaryotes can occur between members of the same "species" as well as between microbes separated by vast taxonomic distances. As such, much prokaryotic genetic diversity is both created and sustained by high levels of HGT. Although HGT can occur for genes in the core-genome component of a pan-genome, it occurs much more frequently among genes in the optional, flex-genome component. In some cases, HGT has become so common that it is possible to think of some "floating" genes more as attributes of the environment in which they are useful rather than as attributes of any individual bacterium or strain or "species" that happens to carry them. For example, bacterial plasmids that occur in hospitals are capable of conferring pathogenicity on any bacterium that successfully takes them up. This kind of genetic exchange can occur between widely unrelated taxa.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "horizontal gene transfer" OR "lateral gene transfer") NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Holobiont

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:31

2448

citations

Holobionts are assemblages of different species that form ecological units. Lynn Margulis proposed that any physical association between individuals of different species for significant portions of their life history is a symbiosis. All participants in the symbiosis are bionts, and therefore the resulting assemblage was first coined a holobiont by Lynn Margulis in 1991 in the book Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation. Holo is derived from the Ancient Greek word ὅλος (hólos) for “whole”. The entire assemblage of genomes in the holobiont is termed a hologenome.

PUBMED QUERY: ( holobiont OR hologenome OR holospecies ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Metagenomics

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:31

50094

citations

While genomics is the study of DNA extracted from individuals — individual cells, tissues, or organisms — metagenomics is a more recent refinement that analyzes samples of pooled DNA taken from the environment, not from an individual. Like genomics, metagenomic methods have great potential in many areas of biology, but none so much as in providing access to the hitherto invisible world of unculturable microbes, often estimated to comprise 90% or more of bacterial species and, in some ecosystems, the bulk of the biomass. A recent describes how this new science of metagenomics is beginning to reveal the secrets of our microbial world: The opportunity that stands before microbiologists today is akin to a reinvention of the microscope in the expanse of research questions it opens to investigation. Metagenomics provides a new way of examining the microbial world that not only will transform modern microbiology but has the potential to revolutionize understanding of the entire living world. In metagenomics, the power of genomic analysis is applied to entire communities of microbes, bypassing the need to isolate and culture individual bacterial community members.

PUBMED QUERY: ( metagenomic OR metagenomics OR metagenome ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Pangenome

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:33

4029

citations

Although the enforced stability of genomic content is ubiquitous among MCEs, the opposite is proving to be the case among prokaryotes, which exhibit remarkable and adaptive plasticity of genomic content. Early bacterial whole-genome sequencing efforts discovered that whenever a particular "species" was re-sequenced, new genes were found that had not been detected earlier — entirely new genes, not merely new alleles. This led to the concepts of the bacterial core-genome, the set of genes found in all members of a particular "species", and the flex-genome, the set of genes found in some, but not all members of the "species". Together these make up the species' pan-genome.

PUBMED QUERY: ( pangenome[TIAB] OR "pan-genome"[TIAB] OR "pan genome"[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Microbial Ecology

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:53

18430

citations

Wikipedia: Microbial Ecology (or environmental microbiology) is the ecology of microorganisms: their relationship with one another and with their environment. It concerns the three major domains of life — Eukaryota, Archaea, and Bacteria — as well as viruses. Microorganisms, by their omnipresence, impact the entire biosphere. Microbial life plays a primary role in regulating biogeochemical systems in virtually all of our planet's environments, including some of the most extreme, from frozen environments and acidic lakes, to hydrothermal vents at the bottom of deepest oceans, and some of the most familiar, such as the human small intestine. As a consequence of the quantitative magnitude of microbial life (Whitman and coworkers calculated 5.0×1030 cells, eight orders of magnitude greater than the number of stars in the observable universe) microbes, by virtue of their biomass alone, constitute a significant carbon sink. Aside from carbon fixation, microorganisms' key collective metabolic processes (including nitrogen fixation, methane metabolism, and sulfur metabolism) control global biogeochemical cycling. The immensity of microorganisms' production is such that, even in the total absence of eukaryotic life, these processes would likely continue unchanged.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "microbial ecology" ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Biofilms

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:40

28360

citations

Wikipedia: Biofilm A biofilm is any group of microorganisms in which cells stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy extracellular matrix that is composed of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). The EPS components are produced by the cells within the biofilm and are typically a polymeric conglomeration of extracellular DNA, proteins, and polysaccharides. Because they have three-dimensional structure and represent a community lifestyle for microorganisms, biofilms are frequently described metaphorically as cities for microbes. Biofilms may form on living or non-living surfaces and can be prevalent in natural, industrial and hospital settings. The microbial cells growing in a biofilm are physiologically distinct from planktonic cells of the same organism, which, by contrast, are single-cells that may float or swim in a liquid medium. Biofilms can be present on the teeth of most animals as dental plaque, where they may cause tooth decay and gum disease. Microbes form a biofilm in response to many factors, which may include cellular recognition of specific or non-specific attachment sites on a surface, nutritional cues, or in some cases, by exposure of planktonic cells to sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. When a cell switches to the biofilm mode of growth, it undergoes a phenotypic shift in behavior in which large suites of genes are differentially regulated.

PUBMED QUERY: ( biofilm[title] NOT 28392838[PMID] NOT 31293528[PMID] NOT 29372251[PMID] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Reynolds Number

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:33

4363

citations

It is well known that relative size greatly affects how organisms interact with the world. Less well known, at least among biologists, is that at sufficiently small sizes, mechanical interaction with the environment becomes difficult and then virtually impossible. In fluid dynamics, an important dimensionless parameter is the Reynolds Number (abbreviated Re), which is the ratio of inertial to viscous forces affecting the movement of objects in a fluid medium (or the movement of a fluid in a pipe). Since Re is determined mainly by the size of the object (pipe) and the properties (density and viscosity) of the fluid, organisms of different sizes exhibit significantly different Re values when moving through air or water. A fish, swimming at a high ratio of inertial to viscous forces, gives a flick of its tail and then glides for several body lengths. A bacterium, "swimming" in an environment dominated by viscosity, possesses virtually no inertia. When the bacterium stops moving its flagellum, the bacterium "coasts" for about a half of a microsecond, coming to a stop in a distance less than a tenth the diameter of a hydrogen atom. Similarly, the movement of molecules (nutrients toward, wastes away) in the vicinity of a bacterium is dominated by diffusion. Effective stirring — the generation of bulk flow through mechanical means — is impossible at very low Re. An understanding of the constraints imposed by life at low Reynolds numbers is essentially for understanding the prokaryotic biosphere.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "reynolds number" ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

DNA Barcoding

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:46

13890

citations

Wikipedia: DNA Barcoding

is a method of species identification using a short section of DNA

from a specific gene or genes. The premise of DNA barcoding is that

by comparison with a reference library of such DNA sections (also

called "sequences"), an individual sequence can be used to uniquely

identify an organism to species, just as a supermarket scanner uses

the familiar black stripes of the UPC barcode to identify an item

in its stock against its reference database. These "barcodes" are

sometimes used in an effort to identify unknown species or parts of

an organism, simply to catalog as many taxa as possible, or to

compare with traditional taxonomy in an effort to determine species

boundaries.

Different gene regions are used to identify the different organismal

groups using barcoding. The most commonly used barcode region for

animals and some protists is a portion of the cytochrome c oxidase I

(COI or COX1) gene, found in mitochondrial DNA. Other genes suitable

for DNA barcoding are the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rRNA often

used for fungi and RuBisCO used for plants. Microorganisms

are detected using different gene regions.

See also: What is DNA barcoding? or

DNA barcoding workflows

PUBMED QUERY: DNA[TIAB] barcode[TIAB] OR barcodes[TIAB] OR barcoding[TIAB] NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Symbiosis

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 02:00

34798

citations

Symbiosis refers to an interaction between two or more different organisms living in close physical association, typically to the advantage of both. Symbiotic relationships were once thought to be exceptional situations. Recent studies, however, have shown that every multicellular eukaryote exists in a tight symbiotic relationship with billions of microbes. The associated microbial ecosystems are referred to as microbiome and the combination of a multicellular organism and its microbiota has been described as a holobiont. It seems "we are all lichens now."

PUBMED QUERY: ( symbiosis[tiab] OR symbiotic[tiab] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Endosymbiosis

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 02:00

6576

citations

A symbiotic relationship in which one of the partners lives within the other, especially if it lives within the cells of the other, is known as endosymbiosis. Mitochondria, chloroplasts, and perhaps other cellular organelles are believed to have originated from a form of endosymbiosis. The endosymbiotic origin of eukaryotes seems to have been a biological singularity — that is, it happened once, and only once, in the history of life on Earth.

PUBMED QUERY: endosymbiont NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Wolbachia

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 02:03

4756

citations

WIKIPEDIA: Wolbachia is a genus of bacteria which "infects" (usually as intracellular symbionts) arthropod species, including a high proportion of insects, as well as some nematodes. It is one of the world's most common parasitic microbes and is possibly the most common reproductive parasite in the biosphere. Its interactions with its hosts are often complex, and in some cases have evolved to be mutualistic rather than parasitic. Some host species cannot reproduce, or even survive, without Wolbachia infection. One study concluded that more than 16% of neotropical insect species carry bacteria of this genus, and as many as 25 to 70 percent of all insect species are estimated to be potential hosts. Wolbachia also harbor a temperate bacteriophage called WO. Comparative sequence analyses of bacteriophage WO offer some of the most compelling examples of large-scale horizontal gene transfer between Wolbachia coinfections in the same host. It is the first bacteriophage implicated in frequent lateral transfer between the genomes of bacterial endosymbionts. Gene transfer by bacteriophages could drive significant evolutionary change in the genomes of intracellular bacteria that were previously considered highly stable or prone to loss of genes overtime. Outside of insects, Wolbachia infects a variety of isopod species, spiders, mites, and many species of filarial nematodes (a type of parasitic worm), including those causing onchocerciasis ("River Blindness") and elephantiasis in humans as well as heartworms in dogs. Not only are these disease-causing filarial worms infected with Wolbachia, but Wolbachia seem to play an inordinate role in these diseases. A large part of the pathogenicity of filarial nematodes is due to host immune response toward their Wolbachia. Elimination of Wolbachia from filarial nematodes generally results in either death or sterility of the nematode.

PUBMED QUERY: wolbachia NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Microbiome Project(s)

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:55

755

citations

For many multicellular organisms, a microscopic study shows that microbial cells outnumber host cells by perhaps ten to one. Until recently, these abundant communities of host-associated microbes were largely unstudied, often for lack of analytical tools or conceptual frameworks. The advent of new tools is rendering visible this previously ignored biosphere and the results have been startling. Many facets of host biology have proven to be profoundly affected by the associated microbiomes. As a result, several large-scale projects — such as the Human Microbiome Project — have been undertaken to jump start an understanding of this critical component of the biosphere.

PUBMED QUERY: "microbiome project" NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Microbiome

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:55

90103

citations

It has long been known that every multicellular organism coexists with large prokaryotic ecosystems — microbiomes — that completely cover its surfaces, external and internal. Recent studies have shown that these associated microbiomes are not mere contamination, but instead have profound effects upon the function and fitness of the multicellular organism. We now know that all MCEs are actually functional composites, holobionts, composed of more prokaryotic cells than eukaryotic cells and expressing more prokaryotic genes than eukaryotic genes. A full understanding of the biology of "individual" eukaryotes will now depend on an understanding of their associated microbiomes.

PUBMED QUERY: microbiome[tiab] NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Human Microbiome

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:54

5048

citations

The human microbiome is the set of all microbes that live on or in humans. Together, a human body and its associated microbiomes constitute a human holobiont. Although a human holobiont is mostly mammal by weight, by cell count it is mostly microbial. The number of microbial genes in the associated microbiomes far outnumber the number of human genes in the human genome. Just as humans (and other multicellular eukaryotes) evolved in the constant presence of gravity, so they also evolved in the constant presence of microbes. Consequently, nearly every aspect of human biology has evolved to deal with, and to take advantage of, the existence of associated microbiota. In some cases, the absence of a "normal microbiome" can cause disease, which can be treated by the transplant of a correct microbiome from a healthy donor. For example, fecal transplants are an effective treatment for chronic diarrhea from over abundant Clostridium difficile bacteria in the gut.

PUBMED QUERY: "human microbiome" NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Squid-Vibrio Symbiosis

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 02:00

487

citations

The small bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes) has a mutually beneficial relationship with bacteria called Vibrio fischeri that live on the squid's underside. The bacteria allow the squid to produce light, which then allows the squid to escape from things that might want to eat it. "The squid emit ventral luminescence that is often very, very close to the quality of light coming from the moon and stars at night," explains Margaret McFall-Ngai, Margaret McFall-Ngai, professor of medical microbiology and immunology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. For fish looking up from below for something to eat, the squid are camouflaged against the moon or the starlight because they don't cast a shadow. "It's like a 'Klingon' cloaking device," she notes. But the Vibrio fischeri don't stay in the squid continuously. Every day, in response to the light cue of dawn, the squid vents 90 percent of the bacteria back into the seawater. "And then, while it's sitting quiescent in the sand, the bacteria grow up in the crypt so that when [the squid] comes out in the evening, it will have a full complement of luminous Vibrio fischeri," says McFall-Ngai.

PUBMED QUERY: ( (squid OR euprymna) AND (vibrio OR symbiosis OR symbiotic OR endosymbiont) ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Origin of Eukaryotes

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:47

687

citations

The evolutionary origin of eukaryotes is a critically important, yet poorly understood event in the history of life on earth. The endosymbiotic origin of mitochondria allowed cells to become sufficiently large that they could begin to interact mechanically with their surrounding environment, thereby allowing evolution to create the visible biosphere of multicellular eukaryotes.

PUBMED QUERY: ("origin of eukaryotes"[TIAB] OR eukaryogenesis OR "appearance of eukaryotes"[TIAB] OR "evolution of eukaryotes[TIAB]") NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Evolution of Multicelluarity

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:47

5434

citations

PUBMED QUERY: ( (evolution OR origin) AND (multicellularity OR multicellular) NOT 33634751[PMID] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Origin of Multicellular Eukaryotes

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:53

4373

citations

PUBMED QUERY: ( (origin OR evolution) AND (eukaryotes OR eukaryota) AND (multicelluarity OR multicellular) NOT 33634751[PMID] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Mitochondrial Evolution

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:59

9583

citations

The endosymbiotic hypothesis for the origin of mitochondria (and chloroplasts) suggests that mitochondria are descended from specialized bacteria (probably purple nonsulfur bacteria) that somehow survived endocytosis by another species of prokaryote or some other cell type, and became incorporated into the cytoplasm.

PUBMED QUERY: ( mitochondria AND evolution NOT 26799652[PMID] NOT 33634751[PMID] NOT 38225003[PMID]) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Energetics and Mitochondrial Evolution

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:59

556

citations

Mitochondria are the energy-producing "engines" that provide the power to drive eukaryotic cells. The energy output of hundreds, or thousands, of mitochondria allowed eukaryotic cells to increase in size 1000-fold, or more, over the size of prokaryotics cells. This increase in size allowed an escape from the constraints of low Reynolds numbers and, for the first time, life could function in a way where mechanism, and thus morphology, mattered. Evolution began to shape morphology, allowing the emergence of the multicellular eukaryotic biosphere — the visible living world.

PUBMED QUERY: ( mitochondria AND evolution AND (energetics OR "energy metabolism") ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Telomeres

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 02:01

13541

citations

Wikipedia: A telomere is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences at each end of a chromosome, which protects the end of the chromosome from deterioration or from fusion with neighboring chromosomes. Its name is derived from the Greek nouns telos (τέλος) "end" and merοs (μέρος, root: μερ-) "part". For vertebrates, the sequence of nucleotides in telomeres is TTAGGG, with the complementary DNA strand being AATCCC, with a single-stranded TTAGGG overhang. This sequence of TTAGGG is repeated approximately 2,500 times in humans. In humans, average telomere length declines from about 11 kilobases at birth to less than 4 kilobases in old age,[3] with average rate of decline being greater in men than in women. During chromosome replication, the enzymes that duplicate DNA cannot continue their duplication all the way to the end of a chromosome, so in each duplication the end of the chromosome is shortened (this is because the synthesis of Okazaki fragments requires RNA primers attaching ahead on the lagging strand). The telomeres are disposable buffers at the ends of chromosomes which are truncated during cell division; their presence protects the genes before them on the chromosome from being truncated instead. The telomeres themselves are protected by a complex of shelterin proteins, as well as by the RNA that telomeric DNA encodes.

PUBMED QUERY: telomere.q.txt NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Drosophila: The Fly Room

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:49

61

citations

In the small "Fly Room" at Columbia University, T. H. Morgan and his students, A. H. Sturtevant, C. B. Bridges, H. J. Muller, carried out the work that laid the foundations of modern, chromosomal genetics. The excitement of those times, when the whole field of genetics was being created, is captured in this book, written by one of those present at the beginning. In a time when genomics and genetics maps are discussed almost daily in the popular press, it is worth remembering that the world's first genetic map was created in 1913 by A. H. Sturtevant, then a sophomore in college. In 1933, Morgan received the Nobel Prize in medicine, for his "discoveries concerning the role played by the chro- mosome in heredity." In the 67 years since, genetics has continued to advance, leaving behind a fascinating history. The year 2000 was the 100th anniversary of the founding of modern genetics with the rediscovery of Mendel' work and it is the year in which the full DNA sequence of the Drosophila genome was obtained. The fruit fly is still at the center of genetic research, just as it was in 1910 when work first began in Morgan's fly room.

PUBMED QUERY: ( 1890:1932[PDAT] AND (drosophila OR gene OR genetic OR map OR chromosome OR mutant OR mutation) AND ( "morgan th"[author] OR "morgan lv"[author] OR "sturtevant AH"[author] OR "bridges CB"[author] OR "muller HJ"[author] ) ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

History of Genetics

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:49

748

citations

PUBMED QUERY: genetics (classical OR mendelian) genetics history[mesh] NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Gregor Mendel

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:49

167

citations

In 1865, Gregor Mendel reported the results of his experiments with peas and in so doing laid the foundations of what has become the modern science of genetics. There are few examples of entire fields having been so clearly founded upon the works of one man.

PUBMED QUERY: mendel[title] AND (gregor OR brno OR versuche OR darwin OR "father of genetics") NOT "James Ross" NOT Antarctic NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Did Mendel Cheat?

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:53

38

citations

In 1936, R. A. Fisher noted that Mendel's results seem to come too close to the expected value too often, leading him to conclude "the general level of agreement between Mendel's expectations and his reported results shows that it is closer than would be expected in the best of several thousand repetitions. The data have evidently been sophisticated systematically..." That is, Mendel's data had been fiddled with. A small industry has grown up, with various authors taking sides on the controversy.

PUBMED QUERY: (mendel[TITLE] OR mendelian[TITLE]) AND (cheat OR "too good"[TITLE] OR fisher OR controversy OR controversies) NOT (Humans[MESH] OR rats[MESH] OR Software[MESH] OR "Mendelian randomization") NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Did Mendel Cheat? (related papers)

updated:

citations

PUBMED QUERY:

Classical Genetics

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:41

1727

citations

Wikipedia: Classical genetics is often referred to as the oldest form of genetics, and began with Gregor Mendel's experiments that formulated and defined a fundamental biological concept known as Mendelian Inheritance. Mendelian Inheritance is the process in which genes and traits are passed from a set of parents to their offspring. These inherited traits are passed down mechanistically with one gene from one parent and the second gene from another parent in sexually reproducing organisms. This creates the pair of genes in diploid organisms. Gregor Mendel started his experimentation and study of inheritance with phenotypes of garden peas and continued the experiments with plants. He focused on the patterns of the traits that were being passed down from one generation to the next generation. This was assessed by test-crossing two peas of different colors and observing the resulting phenotypes. After determining how the traits were likely inherited, he began to expand the amount of traits observed and tested and eventually expanded his experimentation by increasing the number of different organisms he tested.

PUBMED QUERY: 1890:1938[PDAT] AND (genetic OR gene OR genes OR genetics OR heredity OR inheritance OR mutation OR chromosome OR mendel) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Classical Genetics: Drosophila

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:41

943

citations

Wikipedia: Drosophila is a genus of flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many species to linger around overripe or rotting fruit. One species of Drosophila in particular, D. melanogaster, has been heavily used in research in genetics and is a common model organism in developmental biology. The terms "fruit fly" and "Drosophila" are often used synonymously with D. melanogaster in modern biological literature. The entire genus, however, contains more than 1,500 species and is very diverse in appearance, behavior, and breeding habitat. D. melanogaster is a popular experimental animal because it is easily cultured en masse out of the wild, has a short generation time, and mutant animals are readily obtainable. In 1906, Thomas Hunt Morgan began his work on D. melanogaster and reported his first finding of a 'white' (eyed) mutant in 1910 to the academic community. He was in search of a model organism to study genetic heredity and required a species that could randomly acquire genetic mutation that would visibly manifest as morphological changes in the adult animal. His work on Drosophila earned him the 1933 Nobel Prize in Medicine for identifying chromosomes as the vector of inheritance for genes.

PUBMED QUERY: 1890:1953[PDAT] AND drosophila NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Classical Genetics: Mutation

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:41

1529

citations

Wikipedia: We now know that, in biology, a mutation is the process that produces heritable change via the permanent alteration of the nucleotide sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA or other genetic elements. Mutations result from errors during DNA replication or other types of damage to DNA (such as may be caused by exposure to radiation or carcinogens), which then may undergo error-prone repair, or cause an error during other forms of repair, or else may cause an error during replication. Mutations may also result from insertion or deletion of segments of DNA due to mobile genetic elements. Mutations may or may not produce discernible changes in the observable characteristics (phenotype) of an organism. Mutations play a part in both normal and abnormal biological processes including: evolution, cancer, and the development of the immune system, including junctional diversity. In the early days of classical genetics, work to characterize, model, and understand the phenomenology of mutation were critically important for developing the foundations of modern molecular genetics.

PUBMED QUERY: 1859:1953[PDAT] AND (mutation OR mutant OR mutagen) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Long Term Ecological Research

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:52

579

citations

The LTER Network: The US. long-term ecological research network consists of 28 sites with a rich history of ecological inquiry, collaboration across a wide range of research topics, and engagement with students, educators, and community members. Bringing together diverse groups of researchers with sustained data collection, ecosystem manipulation experiments, and modeling, these sites allow scientists to apply new tools and explore new questions in systems where the context is well understood, shared, and thoroughly documented.

PUBMED QUERY: ( LTER OR ("Long Term Ecological Research") ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Ecological Informatics

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:47

12552

citations

Wikipedia: Ecological Informatics Ecoinformatics, or ecological informatics, is the science of information (Informatics) in Ecology and Environmental science. It integrates environmental and information sciences to define entities and natural processes with language common to both humans and computers. However, this is a rapidly developing area in ecology and there are alternative perspectives on what constitutes ecoinformatics. A few definitions have been circulating, mostly centered on the creation of tools to access and analyze natural system data. However, the scope and aims of ecoinformatics are certainly broader than the development of metadata standards to be used in documenting datasets. Ecoinformatics aims to facilitate environmental research and management by developing ways to access, integrate databases of environmental information, and develop new algorithms enabling different environmental datasets to be combined to test ecological hypotheses. Ecoinformatics characterize the semantics of natural system knowledge. For this reason, much of today's ecoinformatics research relates to the branch of computer science known as Knowledge representation, and active ecoinformatics projects are developing links to activities such as the Semantic Web. Current initiatives to effectively manage, share, and reuse ecological data are indicative of the increasing importance of fields like Ecoinformatics to develop the foundations for effectively managing ecological information. Examples of these initiatives are the National Science Foundation's Datanet , DataONE and Data Conservancy projects.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "ecology OR ecological" AND ("data management" OR informatics) NOT "assays for monitoring autophagy" ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Cloud Computing

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:42

4456

citations

Wikipedia: Cloud Computing Cloud computing is the on-demand availability of computer system resources, especially data storage and computing power, without direct active management by the user. Cloud computing relies on sharing of resources to achieve coherence and economies of scale. Advocates of public and hybrid clouds note that cloud computing allows companies to avoid or minimize up-front IT infrastructure costs. Proponents also claim that cloud computing allows enterprises to get their applications up and running faster, with improved manageability and less maintenance, and that it enables IT teams to more rapidly adjust resources to meet fluctuating and unpredictable demand, providing the burst computing capability: high computing power at certain periods of peak demand. Cloud providers typically use a "pay-as-you-go" model, which can lead to unexpected operating expenses if administrators are not familiarized with cloud-pricing models. The possibility of unexpected operating expenses is especially problematic in a grant-funded research institution, where funds may not be readily available to cover significant cost overruns.

PUBMED QUERY: ( cloud[TIAB] AND (computing[TIAB] OR "amazon web services"[TIAB] OR google[TIAB] OR "microsoft azure"[TIAB]) ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Publications by FHCRC Researchers

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:48

27510

citations

The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center began in 1975, with critical help from Washington State's U.S. Senator Warren Magnuson.

Fred Hutch quickly became the permanent home to Dr. E. Donnall Thomas, who had spent decades developing an innovative treatment for leukemia and other blood cancers. Thomas and his colleagues were working to cure cancer by transplanting human bone marrow after otherwise lethal doses of chemotherapy and radiation. At the Hutch, Thomas improved this treatment and readied it for widespread use. Since then, the pioneering procedure has saved hundreds of thousands of lives worldwide.

While improving bone marrow transplantation remains central to Fred Hutch's research, it is now only part of its efforts. The Hutch is home to five scientific divisions, three Nobel laureates and more than 2,700 faculty, who collectively have published more than 10,000 scientific papers, presented here as a full bibliography.

NOTE: From 1995 to 2009 I served as the Hutch's vice president for information technology — hence my interest in the organization. Although my role was in the admin division, if you dig through this bibliography, you will find a couple of papers with me as an author.

PUBMED QUERY: ( fhcrc[Affiliation] OR "fred hutchinson"[Affiliation] OR "Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research"[Affiliation] OR "Fred Hutch"[affiliation] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Invasive Ductal Carcinoma

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:50

10253

citations

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), also known as infiltrating ductal carcinoma, is cancer that began growing in a milk duct and has invaded the fibrous or fatty tissue of the breast outside of the duct. IDC is the most common form of breast cancer, representing 80 percent of all breast cancer diagnoses.

PUBMED QUERY: ("invasive ductal carcinoma" OR IDC) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (etiology and causes)

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:50

3926

citations

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC),

also known

as infiltrating ductal carcinoma, is cancer that

began growing in a milk duct and has invaded the

fibrous or fatty tissue of the breast outside of

the duct. IDC is the most common form of breast

cancer, representing 80 percent of all breast

cancer diagnoses.

The causes of invasive ductal carcinoma have not been conclusively established. Researchers have determined that cancer can form when the cells in a milk-producing duct undergo changes that cause them to grow uncontrollably, divide very rapidly or remain viable longer than they should. The result is an accumulation of excess cells that can form a mass, or tumor, and potentially spread to nearby lymph nodes and distant areas of the body. The underlying reason for those cellular changes, however, remains unclear.

By evaluating the results of extensive studies, scientists have identified certain hormonal, environmental and lifestyle factors that are believed to influence a person's breast cancer risk, such as smoking, poor nutrition and prior radiation therapy administered to the chest area. Even so, it's important to keep in mind that some individuals who have no risk factors develop cancer, while others with one or more risk factors do not. Most likely, the precise cause is a complex interaction of many factors.

In rare cases, the causes of invasive ductal carcinoma have been traced to inherited attributes, such as mutations of the:

(a)

Breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1), a tumor suppressor gene,

(b)

Breast cancer gene 2 (BRCA2), a tumor suppressor gene, or

(c)

ErbB2 gene, which produces the HER2 protein that promotes cellular proliferation.

PUBMED QUERY: ( ("invasive ductal carcinoma" OR IDC) AND (cause OR caused OR etiology) ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Invasive Species

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:51

18387

citations

Standard Definition: Invasive species are plants, animals, or pathogens that are non-native (or alien) to the ecosystem under consideration and whose introduction causes or is likely to cause harm. Although that definition allows a logical possibility that some species might be non-native and harmless, most of time it seems that invasive species and really bad critter (or weed) that should be eradicated are seen as equivalent phrases. But, there is a big conceptual problem with that notion: every species in every ecosystem started out in that ecosystem as an invader. If there were no invasive species, all of Hawaii would be nothing but bare volcanic rock. Without an invasion of species onto land, there would be no terrestrial ecosystems at all. For the entire history of life on Earth, the biosphere has responded to perturbation and to opportunity with evolutionary innovation and with physical movement. While one may raise economic or aesthetic arguments against invasive species, it is impossible to make such an argument on scientific grounds. Species movement — the occurrence of invasive species — is the way the biosphere responds to perturbation. One might even argue that species movement is the primary, short-term "healing" mechanism employed by the biosphere to respond to perturbation — to "damage." As with any healing process, the short-term effect may be aesthetically unappealing (who thinks scabs are appealing?), but the long-term effects can be glorious.

PUBMED QUERY: ("invasive species" OR "invasion biology" OR "alien species" OR "introduced species" ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Sociobiology

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 02:00

1124

citations

Sociobiology is a field of scientific study that is based on the hypothesis that social behavior has resulted from evolution and attempts to examine and explain social behavior within that context. Sociobiology investigates social behaviors, such as mating patterns, territorial fights, pack hunting, and the hive society of social insects. It argues that just as selection pressure led to animals evolving useful ways of interacting with the natural environment, it led to the genetic evolution of advantageous social behavior. While the term "sociobiology" can be traced to the 1940s, the concept did not gain major recognition until the publication of Edward O. Wilson's book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis in 1975.

PUBMED QUERY: sociobiology NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Kin Selection

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:51

1832

citations

Wikipedia: Kin selection is the evolutionary strategy that favours the reproductive success of an organism's relatives, even at a cost to the organism's own survival and reproduction. Kin altruism is altruistic behaviour whose evolution is driven by kin selection. Kin selection is an instance of inclusive fitness, which combines the number of offspring produced with the number an individual can produce by supporting others, such as siblings. Charles Darwin discussed the concept of kin selection in his 1859 book, The Origin of Species, where he reflected on the puzzle of sterile social insects, such as honey bees, which leave reproduction to their mothers, arguing that a selection benefit to related organisms (the same "stock") would allow the evolution of a trait that confers the benefit but destroys an individual at the same time. R.A. Fisher in 1930 and J.B.S. Haldane in 1932 set out the mathematics of kin selection, with Haldane famously joking that he would willingly die for two brothers or eight cousins. In 1964, W.D. Hamilton popularised the concept and the major advance in the mathematical treatment of the phenomenon by George R. Price which has become known as "Hamilton's rule". In the same year John Maynard Smith used the actual term kin selection for the first time. According to Hamilton's rule, kin selection causes genes to increase in frequency when the genetic relatedness of a recipient to an actor multiplied by the benefit to the recipient is greater than the reproductive cost to the actor.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "kin selection" OR "inclusive fitness" ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Genomic Standards Consortium

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:50

41

citations

The Genomic Standards Consortium (GSC) is an open-membership working body formed in September 2005. The aim of the GSC is making genomic data discoverable. The GSC enables genomic data integration, discovery and comparison through international community-driven standards.

PUBMED QUERY: ("genomic standards consortium" AND GSC OR RCN4GSC) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Misophonia — Cannot Stand the Sound of Chewing

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:58

433

citations

Wikipedia: Misophonia, literally "hatred of sound," was proposed in 2000 as a condition in which negative emotions, thoughts, and physical reactions are triggered by specific sounds. It is also called "select sound sensitivity syndrome" and "sound-rage." Misophonia has no classification as an auditory, neurological, or psychiatric condition, there are no standard diagnostic criteria, it is not recognized in the DSM-IV or the ICD-10, and there is little research on its prevalence or treatment. Proponents suggest misophonia can adversely affect ability to achieve life goals and to enjoy social situations. Treatment consists of developing coping strategies such as cognitive behavioral therapy and exposure therapy. As of 2016 the literature on misophonia was very limited (see below). Some small studies show that people with misophonia generally have strong negative feelings, thoughts, and physical reactions to specific sounds, which the literature calls "trigger sounds." One study found that around 80% of the sounds were related to the mouth (eating, yawning, etc.), and around 60% were repetitive.

PUBMED QUERY: ( misophonia OR "sound rage" OR "select sound sensitivity syndrome" ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Hoopoes

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:50

82

citations

Wikipedia: Hoopoes are colourful birds found across Afro-Eurasia, notable for their distinctive "crown" of feathers. Three living and one extinct species are recognized, though for many years all were lumped as a single species — Upupa epops. Formerly considered a single species, the hoopoe has been split into three separate species: the Eurasian hoopoe, Madagascan hoopoe and the resident African hoopoe. One accepted separate species, the Saint Helena hoopoe, lived on the island of St Helena but became extinct in the 16th century. Hoopoes are distinctive birds and have made a cultural impact over much of their range. They were considered sacred in Ancient Egypt, and were "depicted on the walls of tombs and temples". At the Old Kingdom, the hoopoe was used in the iconography as a symbolic code to indicate the child was the heir and successor of his father. They achieved a similar standing in Minoan Crete. In the Torah, Leviticus 11:13-19, hoopoes were listed among the animals that are detestable and should not be eaten. They are also listed in Deuteronomy as not kosher. Hoopoes also appear in the Quran and is known as the "hudhud", in Surah Al-Naml 27:20-22: "And he Solomon sought among the birds and said: How is it that I see not the hoopoe, or is he among the absent? I verily will punish him with hard punishment or I verily will slay him, or he verily shall bring me a plain excuse. But he [the hoopoe] was not long in coming, and he said: I have found out (a thing) that thou apprehendest not, and I come unto thee from Sheba with sure tidings." The sacredness of the Hoopoe and connection with Solomon and the Queen of Sheba is mentioned in passing in Rudyard Kipling's "The Butterfly that Stamped." Islamic literature also states that a hoopoe saved Moses and the children of Israel from being crushed by the giant Og after crossing the Red Sea. The hoopoe is the king of the birds in the Ancient Greek comedy The Birds by Aristophanes. Hoopoes have well-developed anti-predator defences in the nest. The uropygial gland of the incubating and brooding female is quickly modified to produce a foul-smelling liquid, and the glands of nestlings do so as well. These secretions are rubbed into the plumage. The secretion, which smells like rotting meat, is thought to help deter predators, as well as deter parasites and possibly act as an antibacterial agent. The secretions stop soon before the young leave the nest. From the age of six days, nestlings can also direct streams of faeces at intruders, and will hiss at them in a snake-like fashion.

PUBMED QUERY: hoopoe OR upupa NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Urolithiasis

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 02:02

1220

citations

Some mineral solutes precipitate to form crystals

in urine; these crystals may aggregate and grow to macroscopic

size, at which time they are known as uroliths (calculi or

stones). Mechanisms involved in stone formation are

incompletely understood in dogs and cats. Regardless of the

underlying mechanism(s), uroliths are not produced unless

sufficiently high urine concentrations of urolith-forming

constituents exist and transit time of crystals within the

urinary tract is prolonged. Clinical signs associated with

urolithiasis are seldom caused by microscopic crystals. However,

formation of macroscopic uroliths in the lower urinary tract

that interfere with the flow of urine and/or irritate the

mucosal surface often results in dysuria, hematuria, and

stranguria. Urethral obstruction is common in male dogs and

cats. It may occur suddenly or may develop throughout days or

weeks. Initially, the animal may frequently attempt to urinate

and produce only a fine stream, a few drops, or nothing. Animals

may also exhibit extreme pain manifested by crying out when

attempting to urinate. Complete obstruction causes uremia within

36–48 hr, which leads to depression, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea,

dehydration, coma, and death within ~72 hr.

NOTE:

Urethral obstruction is an emergency condition, and treatment

should begin immediately.

PUBMED QUERY: ( (canine OR feline) AND (urolithiasis) ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Calcium Metabolism and Urinary Stones

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:41

1657

citations

Wikipedia: Calcium Metabolism

— everybody knows that osteoporosis is a huge threat and that the best way

to reduce the risk of osteoporosis is to take lots of dietary calcium supplements

and vitamin D pills.

OK, exercise is good, too, but that can involve actually

breaking a sweat — something that not everyone wants to do.

But, did you also know that hypercalciuria (too much secreted calcium in the urine) is

associated with a significant increase in the risk for kidney stones? And, you can

easily get hypercalciuria if you pop too many calcium-supplement pills.

Hmmmm.

Nice choice, break a hip or pass kidney stones... What to do? As with most things

biological, reality lies somewhere in the trade-off zone. A quick look at the

literature dealing with calciuria and kidney stones is one way to start.

PUBMED QUERY: (calciuria OR "calcium metabolism") AND (urolith OR "kidney stone" OR "kidney stones" OR "bladder stones" OR stones) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Macular Degeneration

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:52

30886

citations

Wikipedia: Macular Degeneration, also known as age-related macular degeneration (AMD or ARMD), is a medical condition which may result in blurred or no vision in the center of the visual field. Early on there are often no symptoms. Some people experience a gradual worsening of vision that may affect one or both eyes. While it does not result in complete blindness, loss of central vision can make it hard to recognize faces, drive, read, or perform other activities of daily life. Macular degeneration typically occurs in older people, and is caused by damage to the macula of the retina. No cure or treatment restores the vision already lost. Age-related macular degeneration is a main cause of central blindness among the working-aged population worldwide. As of 2022, it affects more than 200 million people globally with the prevalence expected to increase to 300 million people by 2040 as the proportion of elderly persons in the population increases. It is more common in those of European or North American ancestry, and is about equally common in males and females. In 2013, it was the fourth most common cause of blindness, after cataracts, preterm birth, and glaucoma. It most commonly occurs in people over the age of fifty and in the United States is the most common cause of vision loss in this age group] About 0.4% of people between 50 and 60 have the disease, while it occurs in 0.7% of people 60 to 70, 2.3% of those 70 to 80, and nearly 12% of people over 80 years old.

PUBMED QUERY: "macular degeneration"[TIAB] NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Alzheimer Disease — Current Literature

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:36

38514

citations

Alzheimer's disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. In most people with Alzheimer's, symptoms first appear in their mid-60s. Alzheimer's is the most common cause of dementia among older adults. Dementia is the loss of cognitive functioning — thinking, remembering, and reasoning — and behavioral abilities to such an extent that it interferes with a person's daily life and activities. Dementia ranges in severity from the mildest stage, when it is just beginning to affect a person's functioning, to the most severe stage, when the person must depend completely on others for basic activities of daily living. Scientists don't yet fully understand what causes Alzheimer's disease in most people. There is a genetic component to some cases of early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Late-onset Alzheimer's arises from a complex series of brain changes that occur over decades. The causes probably include a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. The importance of any one of these factors in increasing or decreasing the risk of developing Alzheimer's may differ from person to person. This bibliography runs a generic query on "Alzheimer" and then restricts the results to papers published in or after 2017.

PUBMED QUERY: 2024:2026[dp] AND ( alzheimer*[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Alzheimer Disease — Treatment

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:37

49525

citations

Alzheimer's disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. In most people with Alzheimer's, symptoms first appear in their mid-60s. Alzheimer's is the most common cause of dementia among older adults. Dementia is the loss of cognitive functioning — thinking, remembering, and reasoning — and behavioral abilities to such an extent that it interferes with a person's daily life and activities. Dementia ranges in severity from the mildest stage, when it is just beginning to affect a person's functioning, to the most severe stage, when the person must depend completely on others for basic activities of daily living. Scientists don't yet fully understand what causes Alzheimer's disease in most people. There is a genetic component to some cases of early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Late-onset Alzheimer's arises from a complex series of brain changes that occur over decades. The causes probably include a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. The importance of any one of these factors in increasing or decreasing the risk of developing Alzheimer's may differ from person to person. Because of this lack of understanding of the root cause for Alzheimer's Disease, no direct treatment for the condition is yet available. However, this bibliography specifically searches for the idea of treatment in conjunction with Alzheimer's to make it easier to track literature that explores the possibility of treatment.

PUBMED QUERY: ( alzheimer*[TIAB] AND treatment[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:33

51499

citations

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neurone disease (MND) or Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that results in the progressive loss of motor neurons that control voluntary muscles. ALS is the most common form of the motor neuron diseases. Early symptoms of ALS include stiff muscles, muscle twitches, and gradual increasing weakness and muscle wasting. Limb-onset ALS begins with weakness in the arms or legs, while bulbar-onset ALS begins with difficulty speaking or swallowing. Around half of people with ALS develop at least mild difficulties with thinking and behavior, and about 15% develop frontotemporal dementia. Motor neuron loss continues until the ability to eat, speak, move, and finally the ability to breathe is lost. Most cases of ALS (about 90% to 95%) have no known cause, and are known as sporadic ALS. However, both genetic and environmental factors are believed to be involved. The remaining 5% to 10% of cases have a genetic cause, often linked to a history of the disease in the family, and these are known as genetic ALS. About half of these genetic cases are due to disease-causing variants in one of two specific genes. The diagnosis is based on a person's signs and symptoms, with testing conducted to rule out other potential causes.

PUBMED QUERY: ( ALS*[TIAB] OR "amyotrophic lateral sclerosis"[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis) — Review Papers

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:35

10134

citations

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neurone

disease (MND) or Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative

disease that results in the progressive loss of motor neurons

that control voluntary muscles. ALS is the most common form

of the motor neuron diseases. Early symptoms of ALS include

stiff muscles, muscle twitches, and gradual increasing weakness

and muscle wasting. Limb-onset ALS begins with weakness in

the arms or legs, while bulbar-onset ALS begins with difficulty

speaking or swallowing. Around half of people with ALS develop

at least mild difficulties with thinking and behavior, and

about 15% develop frontotemporal dementia. Motor neuron loss

continues until the ability to eat, speak, move, and finally

the ability to breathe is lost.

Most cases of ALS (about 90% to 95%) have no known cause, and

are known as sporadic ALS. However, both genetic and environmental

factors are believed to be involved. The remaining 5% to 10% of

cases have a genetic cause, often linked to a history of the

disease in the family, and these are known as genetic ALS.

About half of these genetic cases are due to disease-causing

variants in one of two specific genes. The diagnosis is based

on a person's signs and symptoms, with testing conducted to

rule out other potential causes.

Tens of thousands of papers have been published on ALS.

In this bibliography we restrict our attention to review

papers.

PUBMED QUERY: ( ( ALS*[TIAB] OR "amyotrophic lateral sclerosis"[TIAB] OR "motor neurone disease"[TIAB] ) AND review[SB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis) — Treatment

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:36

8413

citations

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neurone

disease (MND) or Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative

disease that results in the progressive loss of motor neurons

that control voluntary muscles. ALS is the most common form

of the motor neuron diseases. Early symptoms of ALS include

stiff muscles, muscle twitches, and gradual increasing weakness

and muscle wasting. Limb-onset ALS begins with weakness in

the arms or legs, while bulbar-onset ALS begins with difficulty

speaking or swallowing. Around half of people with ALS develop

at least mild difficulties with thinking and behavior, and

about 15% develop frontotemporal dementia. Motor neuron loss

continues until the ability to eat, speak, move, and finally

the ability to breathe is lost.

Most cases of ALS (about 90% to 95%) have no known cause, and

are known as sporadic ALS. However, both genetic and environmental

factors are believed to be involved. The remaining 5% to 10% of

cases have a genetic cause, often linked to a history of the

disease in the family, and these are known as genetic ALS.

About half of these genetic cases are due to disease-causing

variants in one of two specific genes. The diagnosis is based

on a person's signs and symptoms, with testing conducted to

rule out other potential causes.

There is no known cure for ALS. The goal of treatment is to

slow the disease and improve symptoms.

However, this bibliography specifically searches

PubMed for the idea of treatment in conjunction with ALS to

make it easier to track literature that explores the possibility

of treatment.

PUBMED QUERY: ( ( ALS*[TIAB] OR "amyotrophic lateral sclerosis"[TIAB] OR "motor neurone disease"[TIAB] ) AND treatment[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Diverticular Disease

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:46

3864

citations

Diverticular disease is the general name for a common condition that involves small bulges or sacs called diverticula that form from the wall of the large intestine (colon). Although these sacs can form throughout the colon, they are most commonly found in the sigmoid colon, the portion of the large intestine closest to the rectum. Diverticulosis refers to the presence of diverticula without associated complications or problems. The condition can lead to more serious issues including diverticulitis, perforation (the formation of holes), stricture (a narrowing of the colon that does not easily let stool pass), fistulas (abnormal connection or tunneling between body parts), and bleeding. Diverticulitis refers to an inflammatory condition of the colon thought to be caused by perforation of one of the sacs. Several secondary complications can result from a diverticulitis attack, and when this occurs, it is called complicated diverticulitis.

PUBMED QUERY: "Diverticular disease"[tiab] NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

N-Acetyl-Cysteine: Wonder Drug?

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:59

13459

citations

Wikipedia: Acetylcysteine,

also known as N-acetylcysteine (NAC), is a medication that is used to treat paracetamol overdose and to loosen thick mucus in individuals with chronic bronchopulmonary disorders like pneumonia and bronchitis. It has been used to treat lactobezoar in infants. It can be taken intravenously, by mouth, or inhaled as a mist. Some people use it as a dietary supplement.

Common side effects include nausea and vomiting when taken by mouth. The skin may occasionally become red and itchy with any route of administration. A non-immune type of anaphylaxis may also occur. It appears to be safe in pregnancy. For paracetamol overdose, it works by increasing the level of glutathione, an antioxidant that can neutralise the toxic breakdown products of paracetamol. When inhaled, it acts as a mucolytic by decreasing the thickness of mucus.

NAC, as a commercially available dietary supplement, is touted as A potent antioxidant that supports comprehensive wellness, including lung, liver, kidney and immune function.

Is NAC a life-extending wonder drug? What does the scientific literature say?

PUBMED QUERY: nac acetylcysteine OR "acetyl-cysteine" NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Paleonotology Meets Genomics — Sequencing Ancient DNA

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:59

3696

citations

The ideas behind Jurassic Park have become real, kinda sorta. It is now possible to retrieve and sequence DNA from ancient specimens. Although these sequences are based on poor quality DNA and thus have many inferential steps (i,e, the resulting sequence is not likely to be a perfect replica of the living DNA), the insights to be gained from paleosequentcing are nonetheless great. For example, paleo-sequencing has shown that Neanderthal DNA is sufficiently different from human DNA as to be reasonably considered as coming from a different species.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "ancient DNA"[TIAB] OR "ancient genome"[TIAB] OR paleogenetic OR paleogenetics OR paleogenomics OR "DNA,ancient"[MESH]) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Neanderthals

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:59

1662

citations

Wikipedia: Neanderthals or Neandertals — named for the Neandertal region in Germany — were a species or subspecies of archaic human, in the genus Homo. Neanderthals became extinct around 40,000 years ago. They were closely related to modern humans, sharing 99.7% of DNA. Remains left by Neanderthals include bone and stone tools, which are found in Eurasia, from Western Europe to Central and Northern Asia. Neanderthals are generally classified by paleontologists as the species Homo neanderthalensis, having separated from the Homo sapiens lineage 600,000 years ago, but a minority consider them to be a subspecies of Homo sapiens (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis). Several cultural assemblages have been linked to the Neanderthals in Europe. The earliest, the Mousterian stone tool culture, dates to about 160,000 years ago. Late Mousterian artifacts were found in Gorham's Cave on the south-facing coast of Gibraltar. Compared to Homo sapiens, Neanderthals had a lower surface-to-volume ratio, with shorter legs and a bigger body, in conformance with Bergmann's rule, as an energy-loss reduction adaptation to life in a high-latitude (i.e. seasonally cold) climate. Their average cranial capacity was notably larger than typical for modern humans: 1600 cm3 vs. 1250-1400 cm3. The Neanderthal genome project published papers in 2010 and 2014 stating that Neanderthals contributed to the DNA of modern humans, including most humans outside sub-Saharan Africa, as well as a few populations in sub-Saharan Africa, through interbreeding, likely between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago.

PUBMED QUERY: ( Neanderthal[TIAB] OR Neandertal[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

The Denisovans, Another Human Ancestor

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:59

311

citations

Wikipedia: The Denisovans are an extinct species or subspecies of human in the genus Homo. In March 2010, scientists announced the discovery of a finger bone fragment of a juvenile female who lived about 41,000 years ago, found in the remote Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in Siberia, a cave that has also been inhabited by Neanderthals and modern humans. Two teeth belonging to different members of the same population have since been reported. In November 2015, a tooth fossil containing DNA was reported to have been found and studied. A bone needle dated to 50,000 years ago was discovered at the archaeological site in 2016 and is described as the most ancient needle known. Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of the finger bone showed it to be genetically distinct from the mtDNAs of Neanderthals and modern humans. Subsequent study of the nuclear genome from this specimen suggests that Denisovans shared a common origin with Neanderthals, that they ranged from Siberia to Southeast Asia, and that they lived among and interbred with the ancestors of some modern humans. A comparison with the genome of a Neanderthal from the same cave revealed significant local interbreeding with local Neanderthal DNA representing 17% of the Denisovan genome, while evidence was also detected of interbreeding with an as yet unidentified ancient human lineage.

PUBMED QUERY: ( denisovan[TIAB] OR denisova[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Homo floresiensis, The Hobbit

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:59

127

citations

Wikipedia: Homo floresiensis ("Flores Man"; nicknamed "hobbit" for its small stature) is an extinct species in the genus Homo. The remains of an individual that would have stood about 3.5 feet (1.1 m) in height were discovered in 2003 at Liang Bua on the island of Flores in Indonesia. Partial skeletons of nine individuals have been recovered, including one complete skull, referred to as "LB1".These remains have been the subject of intense research to determine whether they represent a species distinct from modern humans. This hominin had originally been considered to be remarkable for its survival until relatively recent times, only 12,000 years ago. However, more extensive stratigraphic and chronological work has pushed the dating of the most recent evidence of their existence back to 50,000 years ago. Their skeletal material is now dated to from 100,000 to 60,000 years ago; stone tools recovered alongside the skeletal remains were from archaeological horizons ranging from 190,000 to 50,000 years ago. Fossil teeth and a partial jaw from hominins believed ancestral to H. floresiensis were discovered in 2014 and described in 2016. These remains are from a site on Flores called Mata Menge, about 74 km from Liang Bua. They date to about 700,000 years ago and are even smaller than the later fossils. The form of the fossils has been interpreted as suggesting that they are derived from a population of H. erectus that arrived on Flores about a million years ago (as indicated by the oldest artifacts excavated on the island) and rapidly became dwarfed. The discoverers (archaeologist Mike Morwood and colleagues) proposed that a variety of features, both primitive and derived, identify these individuals as belonging to a new species, H. floresiensis, within the taxonomic tribe of Hominini, which includes all species that are more closely related to humans than to chimpanzees. Based on previous date estimates, the discoverers also proposed that H. floresiensis lived contemporaneously with modern humans on Flores. Two orthopedic researches published in 2007 reported evidence to support species status for H. floresiensis. A study of three tokens of carpal (wrist) bones concluded there were differences from the carpal bones of modern humans and similarities to those of a chimpanzee or an early hominin such as Australopithecus. A study of the bones and joints of the arm, shoulder, and lower limbs also concluded that H. floresiensis was more similar to early humans and other apes than modern humans. In 2009, the publication of a cladistic analysis and a study of comparative body measurements provided further support for the hypothesis that H. floresiensis and Homo sapiens are separate species.

PUBMED QUERY: ( "Homo floresiensis"[TIAB] ) NOT pmcbook NOT ispreviousversion

Feathered Dinosaurs

updated: 25 Feb 2026 at 01:46

260

citations